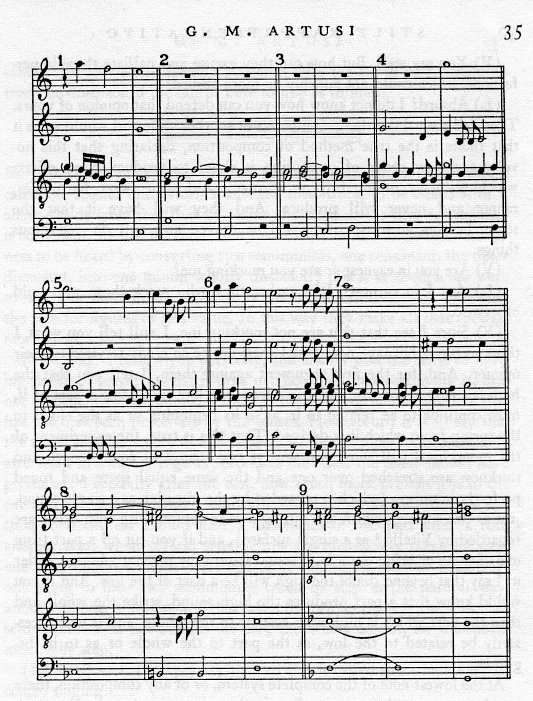

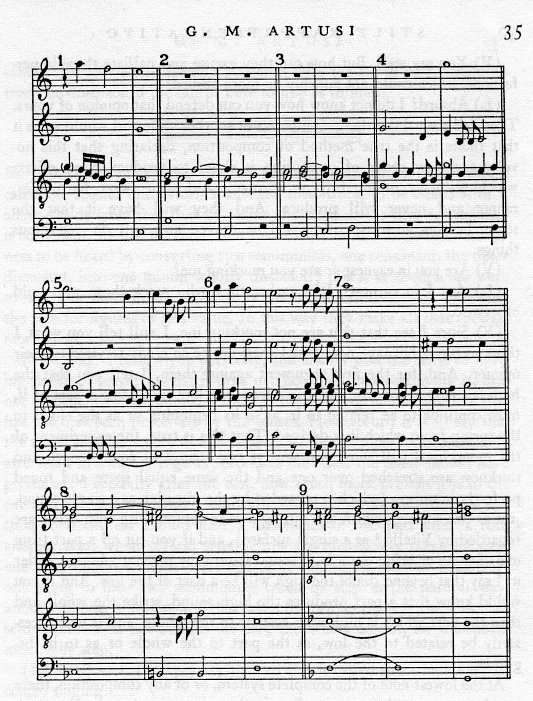

Passage 2

Passage 3

Passage 4

Passage 5

Passage 6

Passage 7

Passage 8

Passage 9

Second Discourse

The dawn of the seventeenth day was breaking as Signor Luca left his house and proceeded toward the monastery of the reverend fathers of Santa Maria del Vado where dwelt Signor Vario, in the service of the Most Illustrious and Reverend Signor the Cardinal Pompeo Arigoni, truly the most illustrious for the many virtues, the goodness, the justice and the piety in which in that Most Illustrious and Reverend Signor universally shine in the service of persons of every quality. On his reaching the monastery, his arrival was announced to Signor Vario, who indeed was momentarily expecting him. Signor Vario immediately left his room and met Signor Luca at the head of the stairs, from whence, after due ceremonies and salutation, they went again to carry on their discussion, according to the arrangement adopted the day before, into a room sufficiently remote and conveniently free from disturbing sounds. After they had seated themselves, Signor Luca began.

Luca:Yesterday, sir, after I had left Your Lordship and was going toward the Piazza, I was invited by some gentlemen to hear certain new madrigals. Delighted by the amiability of my friends and by the novelty of the compositions, I accompanied them to the house of Signor Antonio Goretti, a nobleman of Ferrara, a young virtuoso and as great a lover of music as any man I have ever known. I found there Signor Luzzasco and Signor Hippolito Fiorini, distinguished men, with whom had assembled many noble spirits, versed in music. The madrigals were sung and repeated without giving the name of the author. The texture was not unpleasing. But, as Your Lordship will see, insofar as it introduced new rules, new modes, and new turns of phrase, these were harsh and little pleasing to the ear, nor could they be otherwise; for so long as they violate the good rules - in part founded upon experience, the mother of all things, in part observed in nature, and in part provided by demonstration - we must believe them deformations of the nature and propriety of true harmony, far removed from the object of music, which, as Your Lordship said yesterday, is delectation.

But, in order that you may see the whole question and give me your judgment, here are the passages, scattered here and there through the above mentioned madrigals, which I wrote out yesterday evening for my amusement.

Vario: Signor Luca, you bring me new things which astonish me not a little. It pleases me, at my age, to see a new method of composing, though it would please me much more if I saw that these passages were founded upon some reason which could satisfy the intellect. But as castles in the air, chimeras founded upon sand, these novelties do not please me; they deserve blame, not praise. Let us see the passages, however.

|

Passage 1 Passage 2 Passage 3 Passage 4 Passage 5 Passage 6 Passage 7 Passage 8 Passage 9 |

I hereby present to Your Grace this group of madrigals I have created....

Do not be surprised at my publishing these madrigals without first replying to the objections raised by Artusi to a few tiny portions of them. Since I am in the service of His Grace the Duke of Mantua, I do not have the necessary time at my disposal. Nevertheless, I have written the reply to show what I do is not done by accident. As soon as my reply is copied out it will be published under the title Seconda Pratica, overo Perfettione Della Moderna Musica. Some people may marvel at this, thinking that there is no other practice than the one taught by Zarlino [Giuseppe Zarlino, 1517 - 1590, codifier of the old Netherlandish style, exemplified by Josquin]; but they can be sure that, with regard to consonances and dissonances, there is yet another point of view which defends modern compositional practice to the satisfaction of both the mind and the senses. I wanted to tell you this both to keep others from preempting my expression "Second practice," and so that even ingenious persons may meanwhile countenance other new viewpoints on harmony. Believe me, the modern composer is building upon the foundations of truth.

Live happily.

Some months ago a letter of my brother Claudio Monteverdi was printed [the dedication to Book Five of Madrigals] and given to the public. A certain person, under the fictitious name of Antonio Braccini da Todi, has been at pains to make this seem to the world a chimera and a vanity. For this reason, impelled by the love I bear my brother and still more by the truth contained in his letter, and seeing that he pays attention to deeds and takes little notice of the words of others, and being unable to endure that his works should be so unjustly censured, I have determined to reply to the objections raised against them, declaring in fuller detail what my brother, in his letter, compressed into little space, to the end that this person and whoever follows him may learn that the truth that it contains is very different from what he represents in his discussions. The letter says:...

"Nevertheless, I have written the reply to show what I do is not done by accident."

My brother says that he does not compose his works at haphazard because, in this kind of music, it has been his intention to make the words the mistress of the harmony and not the servant, and because it is in this manner that his work is to be judged in the composition of the melody. Of this Plato speaks as follows: "The song is composed of three things: the words, the harmony, and the rhythm"; and a little further on: "And so of the apt and the unapt, if the rhythm and the harmony follow the words, and not the words these." Then, to give greater force to the words, he continues: "Do not the manner of the diction and the words follow and conform to the disposition of the soul?" and then: "Indeed, all the rest follows and conforms to the diction." But in this case, Artusi takes certain details, or, as he calls them "passages" from my brother's madrigal Cruda Amarilli, paying no attention to the words, but neglecting them as though they had nothing to do with the music, later showing the said "passages" deprived of their words, of all their harmony and of their rhythm. But if, in the "passages" noted as false, he had shown the words that went with them, them the world would not have said that they were chimeras and castles in the air from their entire disregard of the rules of the First Practice. But it would have certainly been a beautiful demonstration if he had done the same with ... others whose harmony obeys their words exactly and which would indeed be left bodies without soul if they were left without this most important and principal part of music, his opponent implying, by passing judgment on these "passages" without the words, that all excellence and beauty consist in the exact observance of the aforesaid rules of the First Practice, which makes the harmony mistress of the words. This my brother will make apparent, knowing for certain that in a kind of composition such as this of his, music turns on the perfection of the melody, considered from which point of view the harmony, from being the mistress, becomes the servant of the words, and the words the mistress of the harmony, to which way of thinking the Second Practice, or modern usage, tends. Taking this as a basis, he promises to show, in refutation of his opponent, that the harmony of the madrigal Cruda Amarilli is not composed at haphazard, but with beautiful art and excellent study, unperceived by his adversary and unknown to him....

Because his opponent seeks to attack the modern music and to defend the old. These are indeed different from one another in their manner of employing the consonances and dissonances, as my brother will make apparent. And since this difference is unknown to the opponent, let everyone understand what the one is and what the other, in order that the truth of the matter may be more clear. Both are honored, revered and commended by my brother. To the old music he has given the name the First Practice from its being the first practical usage, and the modern music he has called Second Practice from its being the second practical usage.

By First Practice he understands the one that turns on the perfection of the harmony, that is, the one that considers the harmony not commanded, but commanding, not the servant, but the mistress of the words, and this was founded by those men who composed in our notation music for more than one voice, was then followed and amplified by ... Josquin Desprez ... and others of those times, ...

By Second Practice, ... he understands the one that turns on the perfection of the melody, that is, the one that considers harmony not commanding, but commanded, and makes the words the mistress of the harmony. For reason of this sort he has called it "second," and not "new," and he has called it "practice," and not "theory," because he understands its explanation to turn on the manner of employing the consonances and dissonances in actual composition.

Believe me, the modern composer is building upon the foundations of truth.

Live happily.

My brother, knowing that, because of the command of the words, modern composition does not and cannot observe the rules of practice and that only a method of composition that takes account of this command will be so accepted by the world that it may justly be called a usage, has said this because he cannot believe and never will believe - even if his own arguments are insufficient to sustain the truth of such a usage - that the world will be deceived, even if his opponent is. And farewell.