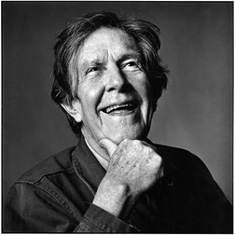

Photo Credit: Steven Gunther

Article on Music of Changes at the John Cage database.

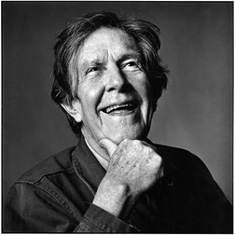

Photo Credit: Steven Gunther |

Few artists have as strong an influence on their fields as John Cage. Cage may best be considered as a "polyartist," an invented term for one who has excelled in numerous unrelated artistic fields; in this case: music, theater, literature and visual arts. In his eminently readable book, "John Cage (ex)plain(ed)," critic Richard Kostelanitz writes that Cage's "principal theme, applicable to all arts, was the denial of false authority by expanding the range of acceptable and thus employable materials, beginning with nonpitched "noises," which he thought should be heard as music 'whether we're in or out of the concert hall.'" To this end, Cage developed and explored a number of devices, all remarkably original, from the prepared piano, a piano whose strings have been altered with all manner of devices and thus produces sounds unexpected from such an instrument; to the addition of chance to the composition process (as in Music of Changes) or the performance itself (as in, among others, his work for twelve radios, Imaginary Landscape); to the glorification of simultaneity a la Ringling's three ring circus - in works such as Europera. In works such as these no one event has any more importance than any other event; meaning can only be construed at the listeners will. |